Overview of Outside-In TDD

Beyond Traditional TDD

Traditional test-driven development is a process that is specifically about unit tests: you create objects and call functions and methods. It's sometimes referred to as "middle-out TDD", because you start in the middle of your application building domain logic. This exclusive focus on unit tests comes with a few tradeoffs.

First, because middle-out TDD works at the level of objects and functions, it doesn't address testing your UI. When TDD was created, UI testing technology was immature, unreliable, and difficult to use, so it wasn't incorporated into the process. Today we have better technologies for UI testing, especially on the web—ones that are more reliable, stable, and feasible for developers to write. But because these kinds of tests didn't exist at the inception of traditional TDD, it doesn't provide any guidance on how to incorporate end-to-end tests into your TDD workflow.

Another downside of middle-out TDD is the risk of building functionality that is unused or difficult to use. Say you put a lot of effort TDDing a module for handling data, and then you prepare to integrate it with the rest of your application. Maybe it turns out your data needs to be stored elsewhere, so you don't actually need the module you put so much effort into. Or maybe you discover that in order for your application to use the module it needs to have a different interface than the one you built it with, and you have to rework it.

Finally, a tradeoff of the middle-out approach is that it usually (but not necessarily) involves testing code in integration with its dependencies—the other code it works with in production. The upside of this approach is that it can catch bugs in how modules integrate with one another. But it also means that a bug in one lower-level module can cause failures in the tests of many higher-level modules. There can also be a lack of defect localization: the tests aren't able to pinpoint where the problem originates in a lower-level module because they only see the result that comes out of the higher-level module.

To see if we can overcome these downsides to traditional TDD, let's consider an alternate way to approach test-driven development. Referred to as outside-in TDD, it provides a structure for using end-to-end and unit tests together in a complementary way, solving the above problems and providing additional benefits. Let's see how.

The Two-Level TDD Loop

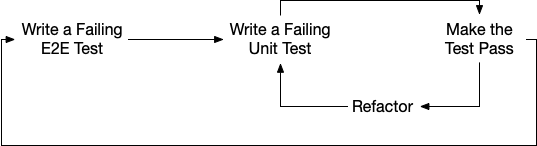

Remember the concept of the TDD loop: red, green, refactor? The first thing outside-in TDD adds is a second TDD loop outside the first one:

- Write an E2E test and watch it fail.

- Step down to a unit test and use the Red-Green-Refactor loop to implement just enough functionality to get past the current E2E test failure.

- Step back up and rerun the E2E test to see if it passes. As long as it still fails, repeat the unit-level loop to address each E2E failure in turn.

These steps can be visualized as a two-level loop:

This style of TDD is called "outside-in" because you start from the outside of your application: the user interface, as tested by the E2E test. Then you step inward to implement the low-level functionality needed to implement the desired outwardly-visible behavior.

Now that we've seen what outside-in TDD entails at a high level, let's look at its component parts to see how they work to address the TDD problems we saw above and provide additional benefits.

The Role of End-to-End Tests

In outside-in TDD, end-to-end tests work together with unit tests, providing test coverage of the same application functionality in a complementary way. Each type of test provides a different value. First let's look at the role of end-to-end tests.

End-to-end tests confirm that your application does what the user wants it to do. At the most basic level, they ensure that the logic you built is actually reachable through the user interface. They also ensure that all the code works together correctly in the context of the running app—the maximum level of test realism. This is sometimes referred to as "external quality:" from the outside, the app works.

End-to-end tests provide a safe way for you make major changes to your app without breaking anything. They're able to do this because as long as the test can still find UI elements that match what it's looking for, everything about the implementation of the app can change. You can replace entire function or object hierarchies, for example if you want to change the technology used for your data layer. You can even reuse the same Cypress tests if you rewrite your application in another framework. Our React and Vue exercises demonstrate this: they have almost identical Cypress tests! For large changes like these, unit tests don't provide a lot of safety because they will fail when units and the ways they interact are replaced.

Another benefit of the end-to-end tests produced by outside-in TDD is that they help you build only what you need. In outside-in TDD, each end-to-end test focuses on one user-facing feature. When you start working on the feature, you write an end-to-end test for it, then you build out the minimum code necessary to get the end-to-end test passing. When it passes, you're done with that feature. This ensures that you only build what is immediately useful to provide functionality to a user. It also prevents code from being written with an interface the app can't use, because you write the code that calls into the module before you write the module itself.

The Role of Unit Tests

With all these benefits of end-to-end tests, is there any need to write unit tests too? Why not stop with the end-to-end tests?

Whereas end-to-end tests confirm the external quality of your app, unit tests expose its "internal quality" by showing how your units are used. The attributes of your code we discussed in "Speed of Development" are all aspects of internal quality. Do your units have clear and simple interfaces? Are they easy to instantiate for tests, or are there a lot of required dependencies that are going to make them harder to change? As your application grows, these factors affect how easy it is to make changes to it—but these factors are invisible to end-to-end tests. You can have an app that works reliably from the outside, but is a mess of spaghetti code on the inside, and that means you'll have trouble handling future change. Unit tests help steer you towards good design attributes that pay off in the long run.

Unit tests also run much more quickly than end-to-end tests, which provides a number of benefits. This speed means you can keep the tests for the module you're working on running continually, so that when you introduce a bug you find out right away. This speeds also makes it feasible to cover every edge case with unit tests, something that isn't realistic with end-to-end tests for a system of any substantial size. This full coverage is what gives you the safety to refactor your code so you can make it better and better over time.

Because of the complementary value of end-to-end and unit tests, outside-in TDDers write both without thinking of it as duplicating effort. Instead, they see that each type of test covers the limitations of the other.

Write the Code You Wish You Had

Since the outside-in TDD process starts from the outside, how can you TDD code that depend on other code that hasn't been written yet? The solution is a practice called "writing the code you wish you had." When you are test-driving one unit of code, think about what functionality belongs in the unit itself and what functionality should be delegated to collaborators (other functions or objects). If that collaborator doesn't already exist, write the code you wish you had: pretend it does exist, and call it the way you'd like to be able to call it. In the test, use test doubles to take the place of that collaborator so you can verify how the unit you're testing interacts with this collaborator.

When you finish test-driving the current unit, your next step is to build any new collaborators that you scaffolded with test doubles. Test-drive the collaborators to match the interface you designed for them in the test of the first unit. Remember, only build the functionality necessary for that collaborator to satisfy the current feature—which might be less than all the functionality you could imagine it to have.

Using test doubles to isolate your units from one another has the benefit of providing good defect localization: when a bug is introduced, your tests will pinpoint which unit has the bug and what exactly is going wrong. To see how this works, let's first consider the case where you aren't using test doubles. Say you have a module A that depends on module B, and in your test of module A you're allowing it to use the real module B. When there is a bug in module B, module A's test will fail even though the problem isn't in module A. Now, what happens if in the test of module A we replace module B with a test double? This changes the meaning of module A's test to "if module B returns the correct result, module A behaves correctly," and because it passes you know that there is no bug in module A itself. Only the test of module B would fail, making it obvious that the problem is in module B.

This kind of test isolation provides even more benefit when a lower-level module is used by many higher-level ones. Say you have ten modules that all depend on module B, and they are tested in integration with module B. If module B has a bug, the tests of all ten higher-level modules would fail, making it hard to identify the underlying cause. Using test doubles, the ten tests for those modules would pass, and only the test for module B would fail—the ideal outcome to help you pinpoint bugs.

It's common to hear criticisms of "mocking" in tests, and in fact those criticisms often apply equally to any kind of test double. Outside-in TDD provides a response to these criticisms by serving as an illustration of how mocks are intended to be used. (In fact, the creators of outside-in TDD are also the creators of mock objects!)

Criticisms of mocks that you might hear include:

- "Mocks make your tests less realistic." Considering the example above, does replacing module B with a test double make the test of module A unrealistic? No, it makes it more focused, testing module A in isolation from other code. True, it doesn't ensure all your units work together—but that's a job best suited to end-to-end tests, not unit tests. By relying on end-to-end tests for integration, you're free to test your units in isolation so you can get the benefits of isolated testing we've discussed.

- "Mocks make your tests more complex because you end up creating mocks that return mocks that return mocks." If that happens, the problem is not with mocks but with the design of the code under test. It reveals that the code has deep coupling to other code. This is a sign that the production code should be changed to have simpler dependencies: specifically, to only call dependencies passed directly to it, so that only one level of mock is needed. Deep coupling is a problem that can be easy to miss when writing the code, but mocks help you see the problem so you can fix it. This is a point in mocks' favor.

What's Next

In this chapter we saw that outside-in test-driven development involves a nested loop where you test-drive a feature with an end-to-end test and build out each necessary piece with a series of unit tests. We saw that end-to-end tests and unit tests work together, the former ensuring the external quality of your app and the latter ensuring the internal quality.

With this, we've completed our survey of agile development practices. The next part of this book is an exercise where we'll put these practices into use to build an app using the frontend framework of your choice.