Why Test-Driven Development?

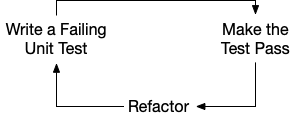

This book will walk you through a number of agile development practices, but it has a particular focus on one such practice: test-driven development. Test-driven development is the practice of writing a test for application functionality before you write the functionality itself. It follows a three-step process, "Red-Green-Refactor":

- Red: write a test for a small bit functionality that does not yet exist, and watch it fail.

- Green: write only enough production code to pass the test.

- Refactor: rearrange the test and production code to improve it without changing its functionality.

Then the cycle repeats: you write a test for the next bit of functionality and watch it fail, etc. This repeating sequence of three steps can be visualized as a loop:

Why would you want to follow test-driven development? There are a number of common problems in programming that test-driven development helps to solve. Let's take a look at some of them.

Regression Safety

As you add new features and make changes to existing features, you need a way to make sure you don't introduce any regressions—unintented changes to the application's functionality. Full manual retesting isn't a scalable solution because it becomes impractical as the application grows larger, so an automated test suite is needed. Most developers who write tests do so after the corresponding production code is complete, an approach called "test-after development." But there are several things that make it difficult to achieve regression safety with test-after development.

First, with test-after development, you may find that some of the production code you wrote is difficult to write a test for. This can happen if your production code has a complex interface or many dependencies on the rest of your application. When a bit of code is designed in a way that is hard to test, developers will often adopt complex testing approaches that attempt to work around the problem. These approaches can be a lot of work and tend to make tests fragile—problems that can lead to giving up on testing the code altogether. Instead, when you find that a bit of code is hard to test, it's better to rearrange the code to make it more testable. (Some would say you shouldn't "design your code for the sake of the tests," but this is really designing the code to make it usable in new contexts, and a test is just one such context.) Rearranging the code can make it more testable, but it can be demotivating to do so because it risks breaking the code before tests can be put in place.

There's a second obstacle to achieving regression safety using test-after development: it makes it difficult to fully specify the functionality of your app. Fully specified means your tests cover every important behavior of your app: if the tests are passing, you can be sure the app is working. But how can you tell if you have enough tests to fully specify the app's functionality? You could try test coverage metrics, which indicate for each function, statement, and branch whether or not it is executed during a test. But metrics can't tell you if you are making assertions about every important result; in fact, you can max out the test coverage metrics without making any assertions at all! Also, when you have complex boolean expressions, metrics don't generally check if you are testing every possible combination of boolean values. Testing every boolean combination is often too many possibilities. Not every boolean combination is important for your application, but some are, and a tool can't make the call which is which: you need to make it yourself. Because of all this, code coverage tools can't guarantee that your application's functionality is fully specified, which can allow bugs to make it to production.

In contrast to these problems with test-after development, test-driven development results in a test suite that provides thorough regression safety for your application. You won't end up with code that can't be tested, because the test is what resulted in that code being written. And by definition TDD results in tests that fully specify your functionality: every bit of logic you've written is the result of a failing test that drove you to write it. Because of this, you can have high confidence that your test suite will catch unintentional changes.

Robust Tests

Even if you see the theoretical value of testing, in practice it may feel like your unit tests have a cost that outweighs their benefit. Sometimes it can seem like whenever you make the smallest change to production code, you need to change the tests as well, and the test changes take more time than the production code changes. Tests are supposed to ensure our changes don't break anything, but if the test fails when we make a change, how much assurance are we really getting?

When a test needs to change every time its production code changes, this is a sign of an over-specified test. Usually what is happening is that the test is specifying details of the production code's implementation. Instead, what we want is a test of the interface or contract of the production code: given a certain set of inputs, what are the outputs and effects visible to the rest of the application? Our test shouldn't care about what's happening inside the module as long as what's happening outside of it stays consistent. When you're testing the interface in this way, you can rearrange a module's implementation code to make it easier to add in a new requirement while the existing tests for that module continue to pass, confirming no existing requirements are broken.

Test-driven development guides you toward testing the interface rather than the implementation, because there is no implementation yet at the time you're writing the test. At that time, it's easy to visualize the inputs and outputs of the production code you want to write, and it's harder to visualize implementation details such as internal state and helper function calls. Because you can't visualize the implementation, you can't write a test that's coupled to it; instead, your test specifies only the interface of the code. This helps you build up a test suite that is less fragile, that doesn't need to change every time production code changes. As a result, the value of your test suite for regression safety goes up and the cost of maintaining it goes down.

Speed of Development

As we discussed in Why Agile?, as applications grow over time, the speed of development tends to get slower and slower. There is more code, so when you need to make a change, more existing code is affected. There is an increasing (sometimes exponentially-increasing) amount of effort needed to add functionality. It's even possible to reach a point where it takes all the developers' effort just to keep the system working, and adding new functionality is impossible.

Why does this slowdown happen? Because when you wrote the code in the first place you couldn't foresee all future requirements. Some new features you add will fit easily into the existing code, but many will not. To get those new features in you have to resort to workarounds that are complex and inelegant but get the job done. As these workarounds multiply, you end up with code that is very difficult to understand and change. Some of your functions end up as massive sequences of unrelated branching logic, and the amount of effort to follow what one of them is doing can be overwhelming.

One way test-driven development speeds up development is by guiding you toward the simplest implementation. We programmers can tend to jump to conclusions by coming up with sophisticated ways to implement a module, but often the needs of an application are simpler than that. TDD leads you to start with a simple implementation and only refactor to a complex one when there are enough tests to force you to do so. If you don't need those tests yet, you don't need that costly complexity that isn't adding value.

Test-driven development also guides you to write the simplest interface. Before you write the implementation of a module, you write the interface presented to the rest of your application for using it. When you write the function call first, you're a lot less likely to end up with a function that takes eight positional arguments and a lot more likely to think of a simpler interface for that function. Interface thinking helps ensure your code presents a clean abstraction to the rest of the application. This reduces the effort required for future developers to understand the calling code, lowering the cost of maintenance.

When you need to add additional functionality, you want to avoid workarounds that will slow you down over time. Instead, you need to adjust the code as you go so that it's easy to add in the new requirement. An ideal regression test suite would give you the confidence to make these changes. But if you have even a little bit of doubt in your test suite, you'll hesitate because you don't want to risk breaking something. Using a workaround will be safer than reorganizing the code. But after an accumulation of many such workarounds you can end up with a codebase that is a mess of giant functions with deeply-nested conditional logic that continues to get slower and more fragile to work with.

With test-driven development, you have a regression test suite you know you can trust, so you can clean up the code any time with very little friction. You can make the code just a bit clearer or simpler, and if the tests are green you will have a high degree of confidence that you haven't broken anything. Over time these tiny improvements add up to a codebase that looks like it was designed from the start knowing what you know now. The simple, clear code helps your development speed stay fast.

Another cause of development slowdown is dependencies. If each part of your code talks to many others then changes are likely to have a ripple effect throughout your codebase: each small change will cascade into many more necessary changes. Code that is easy to change is loosely-coupled, with few dependencies on other bits of code. Why does code end up with many dependencies? One reason is that it's difficult to visualize your code's dependencies in production use. Your application is arranged just so, and all the bits are ready and available for your code to use them—which is not so great when things need to change.

Unit testing reveals the dependencies in your application because they are an instance of reusing your code in a second context. If the code has few dependencies, it will be easy to use on its own and therefore relatively easy to write a test for. But if the code depends on the rest of your application being available, it will be difficult to write a test for it. This difficulty can help you identify a dependency problem, but it won't help you solve that problem. Breaking those dependencies will require changing your code, and you don't yet have the code under test to be able to change it safely.

Test-driven development helps you avoid writing code with too many dependencies in the first place. Because you're writing the test first, you'll quickly see if too many dependencies are required to set up the test, and you can change your strategy before you even write the production code. As a result, you'll end up with code with minimal dependencies. This means that changes you make in one bit of code will be less likely to require changes in many other places in your app, allowing you to deliver features more quickly and smoothly.

When Not to TDD?

Test-driven development provides many benefits, and the argument of this book is that far more projects would benefit from it than are using it today. That said, this doesn't mean TDD is a fit for every software project. Let's look at the cases where TDD might not be such a good fit, but also warnings for each about why you shouldn't make that decision lightly.

Throwaway Code

If your code will be used only a few times and then discarded, there is little need for robustness or evolving the code. This is true if you know for sure the code won't be used on an ongoing basis.

However, many programmers have worked on a project that everyone agreed was "only a proof-of-concept" but nonetheless ends up shipped to production. The risk you take by not TDDing in this case is that if it does end up shipped to production, you will already be started down the path of having code that isn't well-specified by tests.

Rapidly-Changing Organizations

If the business is undergoing frequent fundamental changes, code is more likely to be discarded than evolved, so it isn't valuable to prepare to change that code. An example would be a startup that is pivoting frequently. In systems built for an organization like this, it can be better to limit your test suite to end-to-end tests of the most business-critical flows in the application.

But what about when the business settles down and needs to start evolving on a stable codebase? At this point the code will already be written and it will be difficult to add thorough test coverage you can have confidence in.

Systems That Won't Change

For domains where the needs are well-understood, the system may not evolve much over time. It's a system with a known end state, and once that state is reached further feature changes will be minimal. So if you put effort into getting the initial design right and don't make many mistakes, you won't need to make a lot of changes. I've worked in domains like this.

It's easy to think that things are certain and will never change, because we humans find comfort in certainty. Nonetheless, many programmers' experience is that software often requires more changes than you think it will. And if nothing else, the environment your code runs in will need to change, as operating systems and web browsers are upgraded. And you will at least need to update your underlying libraries for security patches. After any of these changes your application needs to be regression tested, and you will have backed yourself into a corner where you don't have the test coverage ready.

Spikes

Say you have a general idea for a feature, but you don't know exactly how you want it to work. You want to play around with different alternatives to see how they feel before you commit to one. In this approach, you don't know what to specify in a test, and if you did specify something it would likely be thrown out 15 minutes later. So instead, you just write the feature code and see how it works out. This approach is called a "spike,"" and it's looked upon favorably in TDD circles. The question is, once you settle on a final approach, do you keep your untested code as-is, or do you try to retrofit tests around it? TDD advocates would recommend a third option: treat the spike as a learning process, and take those lessons with you as you start over to TDD the code. This takes some extra effort, but when you're familiar with a technology most applications won't require too many spikes: most features are more boring than that!

Human Limitations

One objection to test-driven development is that you can theoretically get all the same benefits just by knowing the above software design principles and being disciplined to apply them. Think carefully about the dependencies of every piece of code. Don't give in to the temptation to code workarounds. In each test you write be sure that every edge case is covered. That seems like it should give you a codebase and test suite that are as good as the ones TDD would give you.

But is this approach practical? I would ask, have you ever worked with a developer who isn't that careful all the time? If not, I'd like to know what League of Extraordinary Programmers you work for! Most of us would agree that most developers aren't that careful all the time. Do you want to write your code in such a way that only the most consistently careful developers are qualified to work on your codebase? That approach leads to an industry that is so demanding that junior developers can't get a job and senior developers are stressed by unrealistic expectations.

Let me ask a more personal question: are you always that careful? Always? Even when management is demanding three number-one priorities before the end of the day? Even when you're sick? Even in the middle of stressful life events or world events?

Programming allows us to create incredibly powerful software with relative ease, and as a result, programmers can be tempted to subconsciously think that they have unlimited abilities. But programmers are still human, and we have limited energy, attention, and patience (especially patience). We can't perform at our peak capacity 100% of the time. But if we accept and embrace our limited capacities, we will look for and rely on techniques that support those limitations.

Test-driven development is one such technique. Instead of thinking about the abstract question "does my code have too many dependencies?", we can just see if it feels difficult to write the test. Instead of asking the abstract "am I testing all the edge cases of the code?", we can focus on the more concrete "what is the next bit of functionality I need to test-drive?" And when we're low on energy and tempted to take shortcuts, our conscience won't remind us about all the big-picture design principles, but it might remind us "right now I would usually be writing the test first."

So can you get all the same benefits of TDD by being disciplined about software design principles? Maybe on your best day. But TDD helps you consistently get those benefits, even on the not-so-good days.

Personal Wiring

In addition to project reasons you might not want to use TDD, there is also a personal reason. The minute-by-minute process of test-driven development is more inherently enjoyable for some people than others. Some developers will enjoy it even on projects where it doesn't provide a lot of benefit, and to other developers it feels like a slog even when they agree it's important for their project. If you fall into the latter group, you might choose to use TDD only on some portions of your codebase where the value is higher and the cost is lower.

As you can probably guess, I fall into the "enjoys TDD" category, so it would be easy for me to say "use TDD for everything." But if you don't enjoy it, I understand choosing to reach for it less frequently. But you're still responsible for the maintainability of your system. You need to be able to make changes without breaking key business functionality, and you probably want to be able to do so without having to do emergency fixes during nights and weekends. You need to be able to keep up the pace of development, and you probably want code that's easy to understand and a joy to work in rather than a tedious chore.

If you aren't using TDD to accomplish those goals, you need to find another way to accomplish them. As we saw in the previous section, "just try harder" isn't an effective strategy because it requires every team member to be operating at peak levels of discipline all the time. And unfortunately I don't have good suggestions for other ways to accomplish those goals. I'm not saying there aren't any; I just don't know them.

It's not fair that TDD and its benefits come more easily to some than others, but it's true. If you're in the latter group, that doesn't make you a worse developer: every developer has different strengths they bring to their team, and TDD isn't the only skill that matters. My encouragement would be this: if you've tried TDD and you feel like it isn't very enjoyable for you, don't assume it will always be that way. Give it a try in the exercise in this book. Practice it on your own. Maybe at some point a switch will flip and you'll find it more motivating. Maybe you'll find a few more parts of your codebase that TDD seems like a fit for.

What's Next

We've just seen how test-driven development works and the benefits it provides. This book will follow a particular kind of TDD approach called outside-in TDD. In the next chapter, we'll see how outside-in TDD builds on the practices we've just examined, providing additional benefits and giving you additional confidence.